TOURIST LIBRARY 9

Castles in Japan

Written by

Prof. N. ORUI, D. Litt. and

Prof. M. TOBA

Published by

BOARD OF TOURIST INDUSTRY,

JAPANESE GOVERNMENT RAILWAYS

Selling Agents by

MARUZEN CO. LTD., TOKYO

JAPAN TOURIST BUREAU TOKYO

Copyright 1935

Total 111 pages

Description

Japanese castles are a unique form of architecture intimately intertwined with the

country's history. Castles were built all around the country by minor feudal lords,

but the most splendid castles that still stand today were built from the late 16th

to early 19th centuries during the time of Oda Nobunaga, Hideyoshi Toyoyomi, and

Ieyasu Tokugawa. The import of firearms into Japan in the 16th century made it possible

for these powerful lords to defeat their rivals and unify the country. At the same time,

it made it necessary for castle fortfications to become bigger and stronger.

These feudal castles were military centers, seats of local government, and centers

of economic activity.

Enjoy these excerpts from Castles in Japan.

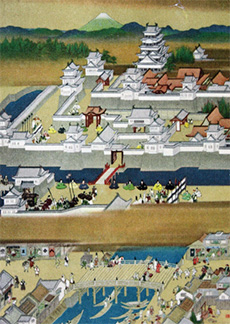

History of Osaka Castle

The castle of Osaka for which Toyotomi Hideyoshi was responsible was built in 1583,

the year following the death of his master, Oda Nobunaga. The city of Osaka occupies

a position of geographical importance, as may be seen from its present position as

the first commercial and industrial city of the country. Nobunaga early had an eye

to this place as the base of his activity, though his idea was not to be realized,

and his mantle, after his unexpected death, fell upon Hideyoshi's shoulders. In his

hands the whole work of unifying the war-worn country went on as if nature herself

were working out her own destiny. The castle of Osaka was begun in 1583 and completed

three years later. It was a castle of far greater dimensions than that of Azuchi and

situated at a place of very much greater importance. At the time of building this

ambitious stronghold at Osaka, Hideyoshi was on the eve of opening his contest with

a number of men of undisputed military strength, each of whom had an eye to the highest

military regency of the country. The whole nation, too, had at this period reached a

state of exuberant energy and vigour, such as it had not seen for ages. As evidence,

for instance, of the time marked by such strong national vitality, attention may be

called to the huge blocks of stone, measuring some score feet in height, used in

building the walls of Osaka Castle, and to the tower-keep designed with eight stories

at an extravagant cost in gold and labour. The tower-keep was roofed with gilded tiles.

Upon the ridge of the topmost roof were placed a pair of dolphins in gold. The walls of

the upper sections were ornamented with designs of cranes and tigers. The crane is

believed in Japan to be a bird capable of living a thousand years, and, for the same reason,

regarded as symbolizing long, unchangeable prosperity. The tiger, considered in the

East as one of the sacred animals, is used to symbolize the paragon of prowess.

An idea may be formed of these decorative designs, when it is known that the country

of this age was in a renascent period of art and literature, as evidenced in the

productions of fine workmanship in the field of arts and industries of the time.

National activity in these fields was amply reflected in the interior ornaments

and decorations of the homes of men of the rising warrior classes of which Hideyoshi

was the most brilliant figure.

Reconstructed tower-keep of Osaka Castle

Castles in peacetime

OPENING CEREMONY OF EDO CASTLE

By. T. Ichihara

When the minor castles were ordered to be done away with, streams of armed men began

to turn away from the defunct citadels in the provinces and pour into the main castles

or their adjoining towns to take up their living quarters, there developed towns and

cities of considerable populations with the feudal castles as their centres.

Under the peaceful conditions of life, which were now the order of the day, commerce

and industry saw great developments. People engaged in these lines, in order to cater

for the demands of the armed classes which were consumers, began to flock around the castles,

eventually to give birth to the quarters formed exclusively for commerce and industry in the

close neighbourhood of the fortified areas. The present towns and cities of Japan, for the most

part, had their foundations laid in such conditions as mentioned above, at one time or another

about three hundred years ago. In some cases the feudal lords, in view of the growing importance

that such commercial and industrial quarters had come to assume in the economic activity

flourishing within their own domains, saw cause to throw up earthworks and ditches around those

parts of their towns.

All these castles were surrendered to the Imperial central government in the second year after

the Restoration, viz. 1869, when the feudal system was abolished. Today it is a rule, however,

to make national treasures of buildings of any importance and to preserve them as such.

Castle geography

These existing castles, from their nature, are situated at points of importance as regards the

local communication of the country they are placed in. Their sites were chosen close to the sea

or large rivers which afford facilities for shipping, the best means of transporting goods.

From their nature as the seats of local government, they were as a rule placed at central parts

of the provinces in which they were built. These considerations were required for military,

economic and strategic reasons.

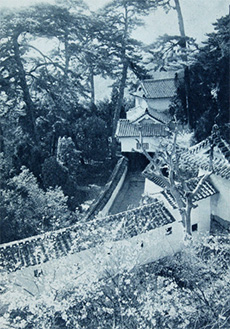

Happy composition of keep, gate and walls

(Himeji Castle)

As the residence and seat of government of a feudatory, and as a town thriving under his patronage,

it was not desirable that the castle should be situated at any place of inaccessible height.

Nevertheless, from the strategic point of view, it was of advantage to choose a lofty location whence

wide, unobstructed views could be commanded. Such a location was also desirable for the artistic

appearances to be imparted to the castle, no less than for the effect that might be produced by its

lofty grandeur upon the minds of the subjects in time of peace or war. As a matter of fact, a hill or

elevation meeting these requirements seldom failed to be chosen for the site of a castle.

The military strategist of those days classified the castles from the topographical features of

their location into the three categories of "castle-on-mountain," "castle-on-plain" and

"castle-on-plain-and-mountain." From the considerations such as those described above, the last-named,

i.e. the strongholds designed by taking advantage of both plain and hill, predominated in number.

This type of castle, historically speaking, was a new product in the course of technical development

by combining the "castles-on-plain" into which the residences on plain ground of feudal lordships had

been developed some several centuries before, with the "castles- on-mountain," which had temporarily

been built in time of war upon eminent peaks marked by strategic advantages afforded by nature.

One of the essential requirements was that the hill or elevation upon which the heart of fortifications

was placed should be isolated from other hills or mountains, or that there should be in its neighbourhood

no high place whence the enemy might look down upon the castle. In case there was no location to fulfil

these requirements a site was chosen on a hill or promontory which looks out over low plains on three sides

and is connected with a hill or mountain on the remaining side. In designing castles the strategists spared

no pains to turn the topographical features of the neighbourhood to the greatest military advantage possible.

With a view to keeping the enemy outside the defensive lines, the sole purpose for which a castle was built

in any case, natural cliffs and sharp rising grounds were in many cases taken advantage of and incorporated

in the plan.

The tallest part of a castle

That which is the largest among the tower structures, and which forms the heart of a castle is

the Tenshu-kaku, kaku meaning a high structure. The Tenshu-kaku, which is not unlike the donjon

or keep seen at a European stronghold, is- not, however, its imitation in any way, but a pure

native architectural production developed in the period between, roughly speaking, 1570 and 1615.

The name tenshu, though identical in sound with the term meaning "master of heaven," by which

Japanese Christians of the 16th century called their god, has in fact nothing to do with the

Christian religion. The term may more properly be regarded as of Buddhist origin, meaning

"heavenly protector" ; an interpretation, in our opinion, not improbable, as may be seen from the

fact that the name Tamonten, the war deity of the same religion, and as the protector of the master

of the castle, is used in designating a particular sort of structure, subordinate to the tower-keep,

as mentioned above.

The Tenshu-kaku, or tower-keeps, were high structures of three and sometimes of as many as seven

stories. Their outward appearances, in some cases, are far from corresponding to the interior designs.

In not a few instances underground compartments were provided within the foundations built with stone.

The tower-keeps were for the following purposes :

- observation of places within and without the castle grounds ;

- commanding station to issue orders to within and without the castle ;

- storing arms and provisions ;

- the last refuge in the event of the castle falling into the hands of the enemy ;

- the living quarters of the castle master in time of war ;

- as a symbol of the acme of the powers commanded by the lord of the castle ;

- as the central mark to which the people within the lord's castle and domain might

turn with loyal minds.

With these aims the tower-keep was built at the centre and the highest point of the castle grounds,

whence might be commanded the most extensive field of vision, rearing its head as the most solid and

lofty structure, like a monarch peak above all else, at such prodigal expense as the lord and master

of the domain could afford.

From an architectural point of view, the tower-keeps are remarkable for the windows and gables arranged

in intricate combination, and for the grandiose scale on which the towers were conceived, features in

both instances not to be met with in any temples of Shinto or Buddhism, or in ordinary residential buildings.

In the towers of more elaborate design the topmost floor was sometimes provided on four sides with a balcony

and its balustrade, and with fanciful-shaped windows called Kato-mado, of which we shall speak more later.

The ridge of the topmost roof was sometimes ornamented with figures of dolphins which, as well as the tiles,

were plated with gold. There are 16 tower-keeps extant, of which those of Nagoya and Himeji are the most typical.

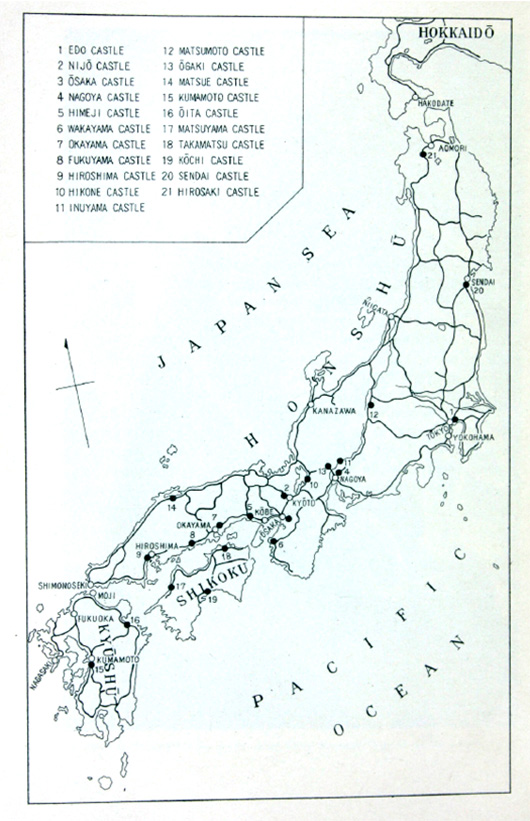

Map of main castles still standing in Japan