There are more than 3,000 different family crests in Japan. They originated in aristocratic

and feudal society in Japan's history, but they can still be seen today in ceremonial

uses such as weddings and funerals. The crests often use natural motifs as symbols.

Crests played a large role in wartime as they were used on banners, shields, and

tents of armies to mark their loyalty. The chrysanthemum and paulownia flowers became

symbols of the Imperial house. In peacetime crests became largely ceremonial and

were also used to decorate daily items.

Kamisimo Bearing Family Crests

Kamisimo is an ordinary ceremonial dress for samurai in the Edo Period.

Japanese heraldry owes its origin and growth to an elegant custom of the court nobles

many centuries ago. Historically, it made its first appearance during the Heian

Period (794-1185), that is about the middle of the 12th century, as the heraldic

devices borne hereditarily by the nobility in the Imperial Court. When the culture

developed among the courtier classes at Kyoto was in its heyday, i.e., in the later

Heian Period, luxury and estheticism prevailed among the court nobles, giving rise

to the elegant custom of adorning the lacquered palanquins and canopied coaches

drawn by oxen, in which the nobles rode on formal visits, with beautiful designs

and patterns of flowers or birds. They vied with one another in the display of those

vehicles thus decorated on the sides, for instance, with artistic patterns of the

tree-peony or iris, or designs of swallows or butterflies. Later, however, those

external decorations came to take on a practical character, being considered a convenience

for distinguishing the crowded palanquins or coaches from one another, and at the

same time a means of demonstrating the honorable lineage of the persons conveyed

by them.

Crest Displayed on Military Flag By the middle of the 13th century, the use of crests

on military flags and pennants had spread among warriors all over the country. This

picture, showing one of the earliest military flags bearing crests, is taken from

the famous Moko Syurai Ekotoba or Mongol Invasion Picture Scroll painted in 1293.

Patterns and designs of flowers and birds were also imprinted on the robes of the

court nobles for decoration, each noble family using the same flower or bird from

generation to generation. In the later periods many family crests were derived from

this source, and contributed much to enriching the heraldic wealth of Japan.

The appearance of the military crest took place in the wake of the family crest

of court nobles. When the warriors were gaining the ascendency over the oligarchy

of the nobility under the leadership of the two clans of Minamoto and Taira, there

were as yet no heraldic emblems to put on their banners, though they fell back on

the two colors, white for the Minamoto and red for the Taira, to represent their

respective camps. However, from the practical need on battlefields to distinguish

at a glance their friends from the enemy, many warriors in various provinces in

the country, belonging to the two leading warrior families, gradually took to carrying

banners with military crests of some kind or other selected by them.

Thus, we deduce that the origin of Japanese heraldry may be traced, on the one hand,

to the esthetic habit prevailing among the court nobles in the Heian Period, and

on the other to the practical needs of warriors for purely military purposes. This

historical background explains therefore the elegance of the heraldic designs developed

among the courtier families and the simplicity of the military crests adopted by

the warriors.

Indicative Reasons

Crests due to these motives are those with some associations or other with the family

name. In no few cases, it is possible, if not always quite accurately, to trace

the family name from the crest borne by a member of the family entitled to bear

the crest. When, for example, the family name is Turu, which means a crane, the

crest is the bird, and when Yosino is the family name, the crest very often may

be of cherry blossom, as Mt. Yosino is so noted for its cherry-trees that the name

is immediately associated with its blossoms.

Kabuki actors' crests as depicted in ukio-e

In the manner of indicating the family name, however, the former is direct, while

the latter is more or less indirect or suggestive. Quite a number among Japanese

family crests belong to the former group, and they ordinarily consist of one or

two characters contained in the family name. For instance, family names like Otaki,

Oisi, etc., which all have the character (大) for the initial, often have a crest

shaped like the character.

Auspicious Reasons

Another form of crests consists of the auspicious symbols that denote longevity,

prosperity, or thriving offspring. As representing the crests belonging to this

category, those of the crane, tortoise and the pine-tree may be cited. From olden

times they have been regarded as highly auspicious, because of the popular belief

that the crane is a bird which lives to the age of one thousand years, the tortoise

enjoys a natural life of ten thousand years, and the pine has ever-green leaves

which resist the severity of climate and which, the more to enhance the auspicious

nature of the tree, affords space to the crane for building its nest. The Imperial

Crest of the Chrysanthemum too originated for auspicious reasons. The chrysanthemum,

also known as enmei-so or a plant of longevity, is believed to have the virtue of

conferring long life upon its eater. Again, on account of the symmetric arrangement

of its yellow petals suggestive of the radiant sun disk, it has been traditionally

prized in this country as the king of flora, under the happy name of nikka, which

literally means a "sun flower."

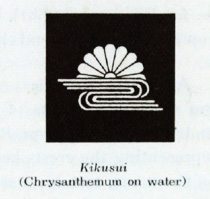

The most famous of all crests, the kikusui or "chrysanthemum on water," borne by

Kusunoki-Masa-sige, a warrior in the 14th century, who is admitted to be the greatest

loyalist of noble character in Japanese history, comes under the same category.

According to an old Chinese tradition, from which the crest of the Kusunoki family

originated, in the unknown past there was in the depth of the mountains in Nanyanghsien

of China a valley overgrown with chrysanthemums, and the people who drank at the

stream running with the floating blossoms all enjoyed longevity.

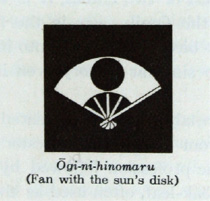

Memorial Reasons

Some crests are reminders of historical events, military or otherwise, of early

ancestors of the family. These may be called memorial crests. One famous crest of

this type may be found in the ogi-ni-hinomaru or "fan with the sun's disk on it,"

worn by the descendants of Nasu-no-Yoiti, a hero in the war between the Minamoto

(or Genzi) and Taira (or Heike) clans at the end of the 12th century. It was during

the historically famous battle fought between the forces of the two rival clans

in the Inland Sea near Yasima, that a boat from Ogi-ni-hinomaru (Fan with the sun's

disk) the Heike fleet slowly drew near the massed Genzi forces during a lull. A

fan with the red sun upon it fixed to the top of a pole stood at the bow of the

boat, young court lady in the waist of the boat was pointing to the fan, giving

a silent challenge to the Genzi warriors to shoot it down. A famous archer called

Nasu- no-Yoiti finally accepted the challenge by order of the Genzi general, Yositune.

Riding into the sea, he took careful aim of the tiny fan which was rocking up and

down a long distance. He prayed for a moment of calm and then let fly his arrow,

which hit the target right in the pivot, tearing off the fan high up in the air.

The stupendous feat was applauded by friend and foe alike. In commemoration of this

military exploit his descendants used a fan with the sun's disk on it as their family

crest.

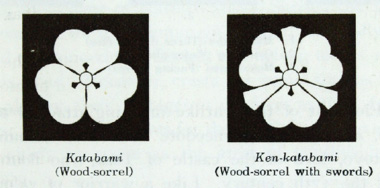

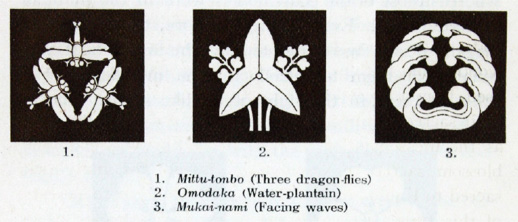

Martial Reasons

There is a type of crest, which has originated from the martial spirit. As a matter

of fact, most of these martial crests constituted the so-called military crests,

whereas those of the court nobles were in the main of esthetic origin. Even when,

therefore, these crests of elegant design were adopted by the warriors, it was usual

with them to introduce some modifications or other to them, in the light of warlike

spirit. One of the most popular of this type is the crest blazoned as ken-katabami—an

attractive combination of the kata-bami or wood-sorrel (Oxalis corniculata), of

aristocratic origin, and the ken or swords as the symbol of warlike spirit.

It was for precisely the same reason that arms such as a bow, an arrow, a helmet

etc. supplied a motive for the family crest. But this was not all. Insects, plants,

and even natural phenomena were sometimes used by the warriors of bygone days as

their crests, if they were attended by some warlike significance. These crests were

represented by the dragon-fly, better known among the warriors by the name katu-musi

or "insect of victory," the omodaka or water-plantain, whose other name was kati-ikusa-sd

or "plant of victory." The wave also serves as the motif of a martial crest.

Eloquent of the warlike meaning attached to the wave, an interesting anecdote is

told of Yamanouti- Kazutoyo, lord of the castle of Tosa, who flourished about the

17th century. Like a warrior of valor, he despised anything with an effeminate flavor.

One day his attention was caught by the crest of the wave worn by one of his retainers.

Thereupon, he severely rebuked him for bearing a crest unworthy of a warrior. But

his answer was that nothing would better conform to the secret of strategy than

the movements of the waves, which alternately beat the shore and retreated from

it. It pleased his lord so much that he asked for this crest of profound significance

for his own use, while giving his thoughtful retainer the crest of tomoe or "comma-

shape" worn by himself.

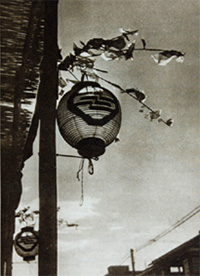

Religious Reasons

Lanterns with Crests At festivals, paper-lanterns bearing the crest of the shrine are usually hung along the street

There are also various crests of a religious character, based either on the Sinto,

Buddhist, Christian or other faiths.

Religious crests associated with the Sinto faith are those borrowing motives from

the messengers of the gods, or the trees and herbs sacred to them. It was no wonder

that faithful devotees of these gods should have used, from a keen desire to seek

their divine protection, their sacred symbols as their family crests. The deer as

the messenger of Kasuga-zinsya Shrine, the plum- blossom sacred to Tenman-gu Shrine,

the hollyhock sacred to Kamo-zinsya Shrine, etc. belong to the crests of this type.

Moreover, crests for some shrines were used also by their devotees as their family

crests. This fact accounts for the crest of a shrine which was widely in vogue as

the crest of families in the locality.

Compared with crests associated with Sinto, those of Buddhist origin are few. They

are mostly of Budhist utensils, and rarely of a nature to symbolize the doctrine

in a more direct way.

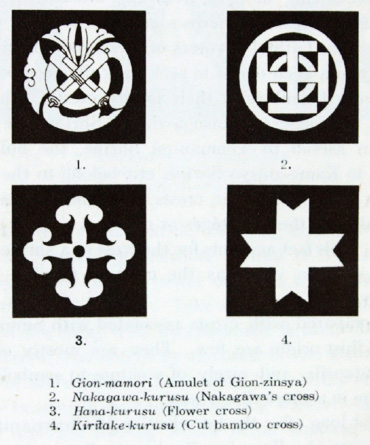

Not long after the introduction of Christianity into this country by Francisco Xavier,

the Portuguese Jesuit, in 1549, the Tokugawa Syogunate rigidly suppressed this Western

religion. However, the faith was secretly followed by ardent followers of the new

creed, who continued to use the cross as their family crest, though often under

some disguise. The crest known as Gion-mamori originates from the cross. It was

originally a crest blazoned after the amulet of Gion-zinsya Shrine, but later as

a variation of the St. Andrew's Cross it was adopted by illegal Christians as their

crest. Another well-known Christian crest is the so-called Nakagawa-kurusuy which

contains the Cross Patent within a double ring. Kurusu is a Japanese corruption

of "cross."