TOURIST LIBRARY 23

Kabuki Drama

Written by

Shutaro Miyake

Published by

JAPAN TRAVEL BUREAU

Copyright 1953, fourth edition

Total 133 pages

Description

Kabuki is a Japanese theatrical art based on song and dance. Developed to capture

popular appeal, it is a feast for the senses in which male actors portray a wide

range of characters with symbolic expressions and lively dance. Types of kabuki

plays include "aragoto" (drama on "masculine" themes), "jidaimono" (historical plays),

"sewamono" (plays on everyday themes from Osaka), and "kizewamono" (similar to sewamono

but coming from Tokyo), and dance pieces. The eighteen plays which were most successful

on the Edo stage are known as "Kabuki Juhachiban" (Eighteen Best Plays).

Please enjoy these excerpts from "Kabuki Drama"

Origins of Kabuki

The Kabuki was first created by an actress by the name of Okuni who lived in Izumo

about four centuries ago. In its original form the Kabuki was not a play, but a

type of primitive dance called Nembutsu Odori, or "prayer dance."

Shortly afterward, the drama was monopolized by male actors, and features of the

Noh, a classical play of music and dance, were incorporated into the Kabuki. The

present stage of development has been attained through the efforts of male players

alone. The earliest period of the Kabuki, when it consisted of dancing only by female

players, was of short duration. After the cast came to be made up entirely by male

players, the Kabuki play was designed to tell a story and it was enriched in its

contents. The foundation of the present-day Kabuki was thus laid in those early

days.

Because of the all-male cast the best-looking actors naturally come to take the

roles of female characters. Such actors are called onnagata, or oyama. This art

of female impersonation by men has made remarkable progress during the past three

centuries. Onnagata are trained for their work from early childhood. Before the

Meiji Restoration (1868), onnagata, dressed in female costume oif the stage as well

as on and every effort was made by them to be like a woman in everyday life. The

result was a marked advance in the art of impersonation making it possible for trained

actors to represent women of all sorts and conditions on the stage. This is one

of the most conspicuous features of the Kabuki play.

A spirited lion (center) sports with the butterflies, flitting about among the peony

flowers—a performance that typifies the symbolism of Kabuki art. This manly dance

of the lion played in the second scene of Kagami Jishi " (see P. 116) contrasts

greatly with the graceful dancing of the pretty maiden acted by the same actor in

the first scene.

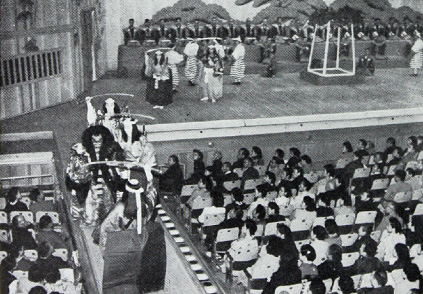

The corridor into the audience, or "Hanamichi"

Hanamichi, or "flower way," is a passage leading to the stage through the left section

of the theater. There is diverse opinion as to the history of the hanamichi, and

no detailed account of it can be given here. Suffice it to say that the hanamichi

has been in use for about two centuries. The passage of the actors on to the stage

over the hanamichi is called de (advance) and the passage back from the stage to

the exit screened with a small curtain termed agemaku, is called hikkomi (withdrawal).

The use of the hanamichi is considered very important and productive of histrionic

effect.

Players on the passage to the stage

The hanamichi is sometimes doubled to enhance the spectacular effect and maintain

closer contact with the audience. The auxiliary passage, kari- hanamichi ("provisional

flower way"), runs parallel on the opposite side of the main passage, and it is

narrower than the hanamichi by about one-third.

The ki and the mie

In the Kabuki, ki or wooden clappers invariably accompany the pulling on and off

of the curtain. Ki or hyoshigi are a pair of square-shaped sticks made of hard kashi

wood. The clapper is about three inches thick and about a foot long. The hyoshigi

are clapped by a kyogenkata, who is a sort of assistant to the stage manager. The

peculiar, sharp sounds of the hyoshigi, like the sound of the bell or the gong of

the Western plays, are used to punctuate the beginning, close, or intervals of a

play. Simple as it may seem, considerable skill is really required for the proper

operation of the hyoshigi.

The Eighteen Best Plays

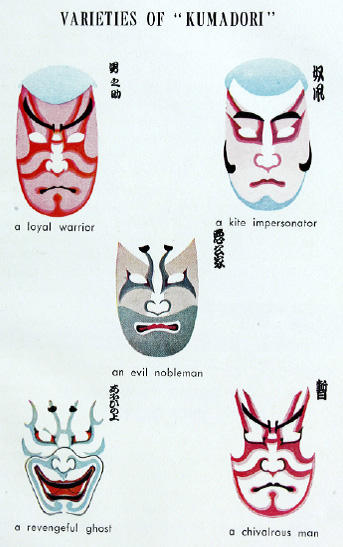

A CHIVALROUS MAN IN " SHIBARAKU," ONE OF "THE EIGHTEEN BEST PLAYS"

Reproduction of the color print by Toyokuni Utagaivo the first (1769- 1825), owned

by the Theatrical Arts Museum at Waseda University

As already mentioned, the eighteen masterpieces selected from the plays of Kabuki

origin staged since the birth of the Kabuki about two centuries and a half ago are

collectively styled "Kabuki Juhachiban." These eighteen were the repertoire of the

nine generations of the illustrious Ichikawas from the first Danjur5 of the Genroku

period (1688—1703) to the ninth in the Meiji era. The plays have been the monopoly

of the Ichikawas, and even now the rights of printing and staging them are in the

hands of the present representive of the family. About ten out of the eighteen are

now staged, the rest having died a natural death. The following seven are considered

by general consent to be of greatest merit:—"Sukeroku" (The Love of Sukeroku, an

Edo Beau), "Kanjinchd" (A Faithful Retainer), "Shiba- raku" (Stop a Minute!), "Yanone"

(The Arrow-head), "Kenuki" (Hair Tweezers), "Narukami" (Thunder), and "Kamahige"

(Shaving with a Large Sickle).

Of these seven, "Sukeroku" and "Kanjincho" are the most distinguished, being the

best of the plays of Kabuki origin. All the plays of the "Kabuki Juhachiban" are

characterized by the spirit of hero-worship, and are labelled Aragoto, or plays

of masculine character, and are theatrical products peculiar to Edo.

Symbolism in kabuki

As has repeatedly been stated, realism and rationalism must not be sought in a Kabuki

play, which is not a play to be heard, but rather a sort of revue to please the

eye. In revues, however, reality and truth are not lost sight of by their writers

in their work of presenting the beautiful. Though there are some exceptions, the

contrary method is used by the Kabuki dramatist. He aims at the beautiful presentation

of the unreal and the unnatural. This point is dwelt on at some length in the following

paragraphs.

There is a well-known play named "Suzugamori," (At Suzugamori), which belongs to

the Kizewamono class. In this play one sees at the opening, when the curtain is

drawn off, a black curtain in the background. This kuromaku, as the black curtain

is called in the language of the Kabuki stage, symbolizes the darkness of night.

The suggestion of a black night is what it is intended to convey, and it is needless

for the spectator to inquire whether it is a rice-field or a hill that is hidden.

In the same scene there is at the right and left a sort of two fold screen called

yabudatami made of bamboo and bamboo twigs. This represents a bamboo grove. Sometimes

a sea is symbolized by a board on which are painted waves—technically called namiita.

It will be seen that, in stage scenery as in other features, the Kabuki play is

essentially symbolic in technique. It is important that the audience should be prepared

to adjust their minds to symbolic representation.

It is related of the fifth Danjuro Ichikawa, one of Japan's stage stars who lived

in Edo more than one hundred years ago, that when taking a meal on the stage he

never used real boiled rice, but instead had some white cotton in the bowl, which

he manipulated so skilfully that the audience was deceived. This shows what his

idea of art was like. The art of Kabuki consists not in making the real look real,

but in making the unreal look real. From this it may be argued that symbolistic

representation is the soul of Kabuki.

Let us take up the case of the mie already explained. The straining of the eyes

and a steady gaze which make up the pose of mie may seem unnatural, but this is

the Kabuki way of emphasizing the senses of excitement,sorrow, and emotion.

In the appreciation of the Kabuki, therefore, one must be richly endowed with imagination;

otherwise one will fail to understand the symbolic and impressionistic expression

of the Kabuki. One must also be a person of great sensibility, who is capable of

perceiving beauty in the apparent grotesqueness and cruelty of a kubijikken or who

discovers a dramatic element in harakiri. Only with such imagination and such sensibility

can one penetrate into a feeling intricate but common to all humanity roughly represented

by a mie, a pose reinforced by the sound of wooden clappers.