TOURIST LIBRARY 6

Japanese Drama

Published by

BOARD OF TOURIST INDUSTRY,

JAPANESE GOVERNMENT RAILWAYS

Selling Agents by

MARUZEN CO. LTD., TOKYO

JAPAN TOURIST BUREAU TOKYO

Total 90 pages

Description

The legendary origin of the Japanese drama is the sacred dance performed before

the heavenly cave, in which the great Ancestral Goddess had hid Herself in the mythological

age of the gods. In Japan one can experience not only the rousing, popular, and

well-known kabuki theater, but also the ancient noh theater as well as the entertaining

bunraku, or puppet theater.

Enjoy these excerpts from "Japanese Drama"

Ancient forms of drama, the forerunners of Noh

Gigaku

During the reign of the Empress Suiko, about 612 A. D., a naturalized citizen named

Mimashi introduced a musical dance from South China. This was greatly encouraged

by Prince Shotoku, the Prince Regent of that time, a man of profound wisdom and

deep faith. It was through him that this dance came to be conducted as part of the

religious ceremonies of Buddhism.

This form was called Gigaku. The masks used in this dance were artistically well

advanced, and may still be seen, preserved in the Shosoin at Nara. It would be an

interesting study to compare these masks with those of early Greece.

Bugaku

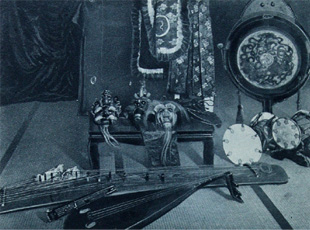

Masks, costumes, and musical instruments used in bugaku

This form appeared a little later than the Gigaku, though still in the period of

Prince Shotoku. Bugaku superseded the Gigaku, and achieved its highest development

in the Heian Period, about 850 A. D. Of course, during these long years there were

various improvements and new creations undertaken, similar to these original dramatic

forms. This Bugaku had two forms, the left and the right. The left form reflected

the traditions of the Chinese and Indian dance ; the right reflected the traditions

of Korea.

In general these may be described as being scenes from ancient tales. They may be

termed the silent drama. In some cases masks were used, in others not. There were

regular locations for the stage, set in the open air. The drama experienced varying

fortunes during these years, but holds a unique position in the world drama as having

survived from that early day. Its character is preserved today in the performance

given by the Music Department of the Imperial Household.

Sangaku

This term, like the two mentioned above, arose from the popular art introduced from

China, and for the most part it consisted of physical feats and humorous acts.

What had formerly been called Sangaku gradually came to be called Sarugaku, its

nature being almost the same as that of the Dengaku. The only difference , was that

in Dengaku the performers were priests, whereas the performers in Sarugaku were

other officers connected with the Shinto shrine. This Sarugaku, as well as the Dengaku,

took over the dramatic elements of Shirabyoshi and Kuse-mai, and made remarkable

progress, such as we can see in the Noh drama of today. That is, it purified itself

by discarding all irrelevancies and retaining its intrinsic elements. This was in

the Muromachi Period, about the year 1370, and was largely due to the efforts of

the father and son, Kwan Ami and Se Ami. What is still more remarkable, these men

combined in one the dramatist, the director and the actor. Se Ami's Dramatic Essay

may well be compared to the Ars Poetica of Aristotle. The comedy which is performed

between the acts of the Noh drama is called Kyogen. This also took on its form during

this period. This Noh and Kyogen became the progenitor of all forms of the later

Japanese drama. It is also a well-known fact that their influence may be seen in

the dramatic writings of Yeats, the British poet.

All the dramatic forms that led up to the above-mentioned Noh and Kyogen were developed

among the noble or the samurai classes ; but, on the contrary, it was the Kabuki

or Shibai, the modern Japanese drama, that had its place among the common people.

Let us remind ourselves that in contrast to the foreign drama, which developed under

the patronage of rulers and nobility, our Japanese drama had to meet the persecution

of the upper classes, reaching its highest development through the enthusiastic

endorsement of the common people.

O Kuni Kabuki and the origin of kabuki theater

The real originator of the Kabuki was a woman, O *Kuni by name. She was born in

Izumo Province, in Central Japan, and her father was a blacksmith connected with

the Izumo Shrine. It is quite likely that she ‘was a priestess to a deity of this

shrine. She was beautiful, clever and skilled in dancing. From about the year 1603

it was customary to erect a stage in the dry bed of the River Kamo, in Kyoto, then

the capital, or beside the Kitano Shrine, and to perform Nembutsu and Kabuki dances

there. As to the nature of O Kuni's dance, it must at first have been a very simple

movement, the dancer wearing a Buddhist garment, striking a gong, and singing Buddhist

chant. This was called the Nembutsu Dance.

But by degrees, and quite naturally, the garments became more ornate, the dancer

wearing a lacquered hat with silk tassels, an outer skirt of bright colour, with

a string of beads around her neck, and dancing to the accompaniment of flute and

drum.

Equally famous was Sanzaburo Nagoya, O Kuni's husband. He had been a ronin, or wandering

knight, leading a dissolute life, when he became attracted to O Kuni. He was himself

possessed of much dramatic ability, and assisted O Kuni to develop her talents to

the highest degree.

O Kuni also played the part of a man, with a sword in her belt, in company with

professional actresses. This was the beginning of modern drama, to which the name

Kabuki was applied. This O Kuni Kabuki was suited to the taste of the times, and

created a great sensation, so that the Shogun of that day (who was practical ruler

of Japan), and the feudal chiefs invited her to perform before them.

O Kuni Kabuki dance, from the "Nara Picture Book"

Suppression of the female kabuki

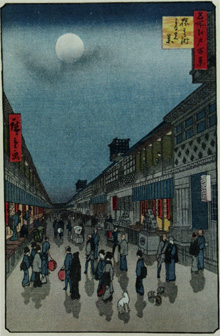

AFTER THE THEATRE IN SARUWAKA STREET, EDO

Theatre-goers leave for home under glorious moonlight (Painted by Hiroshige)

O Kuni, the originator of the Kabuki, was a priestess, but most of the Female Kabuki

players who followed her were courtesans. This was but a natural consequence of

that age, and beyond doubt, it had a demoralizing effect. The dancers came to wear

costumes more and more gay. The music advanced from the simple accompaniment of

flute and drum to that of samisen as well. The stories, too, became more involved,

and the performances more intensely dramatic. As a natural consequence many people

were led astray by these actresses ; fortunes were squandered ; quarrels ensued,

and the evil influences of the stage came to be quite generally recognized. The

Tokugawa Shogun- ate, then in power, could not be blind to this state of affairs,

and in June, 1629, the reigning Shogun, Iye- mitsu, issued a decree strictly prohibiting

all female dancing. Thus, the Female Kabuki came to an untimely end, within thirty

years of its creation by O Kuni.

To be strictly accurate, it must be admitted that actresses did sometimes appear,

but in such cases no male actors were permitted, the male characters being impersonated

by females. There was thus complete sex segregation on the public stage, by governmental

decree. The few female troupes were among the lower classes.

Youth (wakushu) kabuki

The Kabuki of young men came to take the place of the Female Kabuki. This Youth

Kabuki, in its evolution, became the Kabuki of today. Thus, if the Female Kabuki

is called the parent of modern drama, the Youth Kabuki must be called its foster

parent.

The Youth Kabuki had its origin even while the Female Kabuki was at its height.

It was in 1617 that a man called Dansuke began to perform in Kyoto. As the Female

Kabuki sought out the most beautiful women, and by their personal attractiveness

tried to draw great audiences, so this emerging Youth Kabuki sought out handsome

youths with which to attract their patrons. But, as had been the case with the Female

Kabuki, only a short time before this, the Youth Kabuki became exceedingly demoralizing

in its effects. Eventually the government of that day felt that it could be condoned

no longer, and in June, 1652, issued a decree suppressing the Youth Kabuki also.

The suppression decree, just mentioned, was aimed at the elimination of the moral

dangers occasioned by the participation of so many handsome young men in the dramatic

presentations. As these were now forbidden to appear, and as there was a strict

control in the matter of stage morality, the Kabuki Drama underwent a severe trial

at this time.

The authorities treated it like a naughty step-child, kept watch over it as if it

were criminal, and made it the object of petty as well as of major persecutions.

Because of this the history of the stage throughout the Edo Period (1603-1868)—that

of the Tokugawa Shogunate—is a fairly continuous record of hardships. Had it not

possessed the affections of the common people, it might very well have disappeared

along the way.

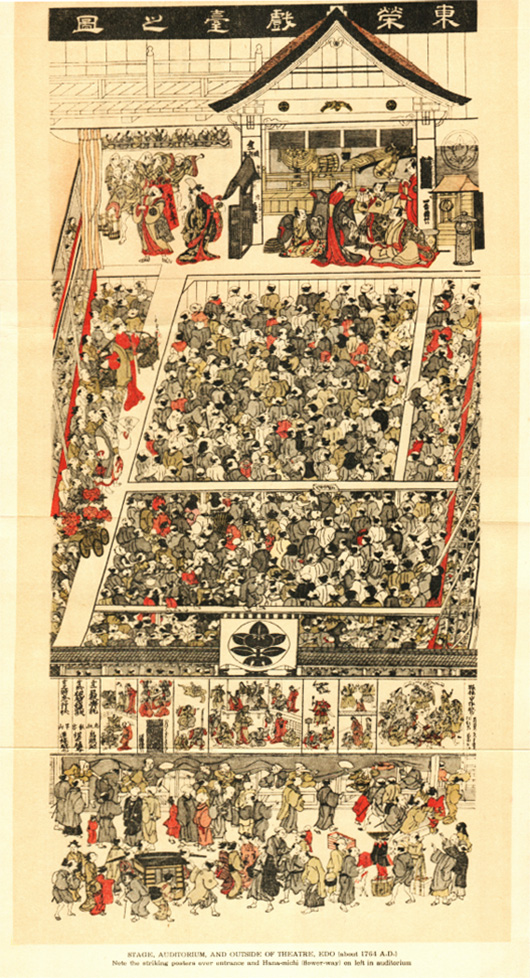

AGE, AUDITORIUM, AND OUTSIDE OF THEATRE, EDO (about 1764 A-D.)

Note the striking posters over entrance and Hana-michi (flower-way) on left in auditorium

While the Kabuki was passing through these experiences a new form of drama was being

born. This was the Puppet Drama. Both of these types had an independent origin,

and generally an independent development, but formed in some respects later a somewhat

intimate connection. It was the Puppet Drama which really invaded the territory

of the Kabuki, and in this form was first known as the Takemoto Drama, from the

name of its leading progenitor.

The Japanese Puppet Drama was performed to the accompaniment of the recitation of

stories, called Joruri. This drama began about the year 1595, but its epoch-making

year was 1685 or thereabouts, when the Takemoto Troupe was formed in Osaka. The

founder of this troupe was a famous story-teller, Gidayu Takemoto. At the time his

performances began he had no professional standing, but he soon gained an enviable

position, and joined forces with the great world-genius, Monzaemon Chikamatsu.

Another of the famous Puppet troupes, and the chief rival of the Takemoto Troupe,

was the Toyotake Troupe, founded by one of the disciples of Gidayu Takemoto, Uneme

by name. His troupe became the strong competitor of that of his former master. The

chief composer, belonging to this troupe, was Ki-no- kaion. He was a genius in dramatic

composition, and naturally enough was Chikamatsu's chief rival.

The fifty-year period from 1710 on, was the golden age of the Puppet Drama in Kyoto

and Osaka ; and during those days the Kabuki was completely overshadowed. Most of

the dramatists of that day allied themselves with one or other of these troupes.

The rise of bunraku, Japanese puppet theater

Bunraku puppets (Photo: Y. Watanabe)

While the Kabuki was passing through these experiences a new form of drama was being

born. This was the Puppet Drama. Both of these types had an independent origin,

and generally an independent development, but formed in some respects later a somewhat

intimate connection. It was the Puppet Drama which really invaded the territory

of the Kabuki, and in this form was first known as the Takemoto Drama, from the

name of its leading progenitor.

The Japanese Puppet Drama was performed to the accompaniment of the recitation of

stories, called Joruri. This drama began about the year 1595, but its epoch-making

year was 1685 or thereabouts, when the Takemoto Troupe was formed in Osaka. The

founder of this troupe was a famous story-teller, Gidayu Takemoto. At the time his

performances began he had no professional standing, but he soon gained an enviable

position, and joined forces with the great world-genius, Monzaemon Chikamatsu.

Another of the famous Puppet troupes, and the chief rival of the Takemoto Troupe,

was the Toyotake Troupe, founded by one of the disciples of Gidayu Takemoto, Uneme

by name. His troupe became the strong competitor of that of his former master. The

chief composer, belonging to this troupe, was Ki-no- kaion. He was a genius in dramatic

composition, and naturally enough was Chikamatsu's chief rival.

The fifty-year period from 1710 on, was the golden age of the Puppet Drama in Kyoto

and Osaka ; and during those days the Kabuki was completely overshadowed. Most of

the dramatists of that day allied themselves with one or other of these troupes.