TOURIST LIBRARY 1

Tea Cult of Japan

Written by

YASUNOSUKE FUKUKITA , Author of " Cha-no-yu, Tea Cult of Japan "

Published by

BOARD OF TOURIST INDUSTRY,

JAPANESE GOVERNMENT RAILWAYS

Copyright 1935, second edition

Total 83 pages

Description

Nothing is more closely associated with the arts and crafts of Japan than Cha-no-yu,

an aesthetic pastime in which powdered green tea is served in a refined atmosphere.

It is a subject which touches on religion, literature and philosophy, as well as

the arts and crafts. But even a cursory familiarity with the tea ceremony is useful

to understand the home life of the Japanese people.

Please enjoy these excerpts from "Tea cult of Japan"

How tea-drinking began

The custom of drinking tea is now universal. Although Oriental in origin, there

is today no Western country where tea is unknown. In Japan the people drink tea

during and after each meal, and it is customary to offer a cup of tea to callers

at any time of the day.

A fine powder of choice green tea is used in Cha-no-yu. To serve powdered tea, it

is put in a bowl much larger than an ordinary tea cup, and hot water is poured over

it. The mixture is beaten by means of a bamboo whisk, which resembles a shaving

brush more than anything else. This practice, which is older in origin, is not in

such common use as the later way of steeping cured leaves in hot water.

Cha-no-yu is peculiar to Japan. It was originally a monastic custom introduced by

Japanese Buddhists who had gone to China for study. It is forgotten in the land

of its origin, and survives in Japan as an aesthetic pastime, a cult in which the

beverage is idealized. Devotees of Cha-no-yu appreciate Art and worship Nature through

the medium of the indescribably delicate and refreshing aroma of powdered tea.

So far as written evidence is concerned, the earliest record of tea-drinking in

Japan takes us back to 729 A. D., in which year the Emperor Shomu is said to have

invited one hundred Buddhist monks to take tea in his palace. It is very likely

that in those days tea was one of the most precious articles imported from China.

It took nearly four centuries for the cultivation of the tea-plant to become popular.

Uji, a district not far from the ancient city of Kyoto, where the best grade of

powdered tea is produced, is indebted to a Japanese monk who brought tea-seeds from

China in the twelfth century. The tea plantations in Shizuoka Prefecture are not

so old as those in Uji, but the export of green tea produced there constitutes an

important item of Japan's foreign trade.

In the north-eastern corner of Kyoto, secluded from the bustling city life, there

is the famous villa where Yoshimasa, eighth Shogun of the Ashikaga line, indulged

in aesthetic pursuits. The historic tea-room built as specified by Shuko, the Father

of the Tea Ceremony, is still preserved in sound condition in the villa, which is

called Ginkaku-ji, better known to foreign tourists as the Silver Pavilion.

The principles of refined and chaste simplicity as taught by Shuko were more concretely

set forth by Jowo (i503-1555), who pleaded for a loftier and more original taste.

Jowd's mantle fell on Sen-no-Soyeki (1521-1591), who is better known by the court

name, "Rikyu," granted through the influence of his patron, Hideyoshi. The formula

and etiquette instituted by Rikyii. still remain the basic practices as taught by

various schools that have sprung up since his death in 1591. Many utensils bearing

the stamp of his genius have come down to the present day, and those who lay out

tea-rooms and gardens still adhere to the canons left by him.

Annex to Ginkakuji, noted for the oldest tea room

In a brochure such as this, it would be out of place to try to show in what way

one school differs from another, but the names of a few principal Ryu, or Schools,

and their originators may be mentioned.

Omote Senke Ryu and Ur a Senke Ryu. were originated by Rikyu's two great-grandsons,

who lived in the same premises in Kyoto. The elder brother occupied the front house,

hence the name of his school " Omote," which means " front." The younger brother

lived in the rear part, and the public gave it the name " Ura," which means "rear,"

in order to distinguish it from the house of the elder brother. There was another

brother, who originated a school of his own, known as " Mushakoji Ryu," so named

after the street where he lived. There are many other schools which various tea-masters

represent in giving lessons, but one is little different from another in their essentials.

Harmony prevails, therefore, when persons of different schools meet at a Cha-no-yu

party.

Of the several feudal lords who were first-class tea-masters and originated their

own systems of ceremonial tea, brief reference may be made to Kobori Masakazu, Lord

of Enshu, whose school is known as " Enshu Ryu." He was the most influential tea-master

and connoisseur of the earlier Tokugawa regime in the seventeenth century. Tea-bowls,

caddies and other articles certified or named by Kobori, as well as those which

were made under his personal direction, are highly prized today. He was also a master

of architecture, landscape gardening and flower arrangement, while he holds a foremost

position in the history of Japan's ceramic art. Some famous gardens laid out by

this aristocrat of versatile genius are still in existence. The influence wielded

by the Lord of Enshu as adviser to Shogun Iyemitsu in the tea ceremony, architecture,

landscape gardening, etc. would make an interesting subject for separate treatment.

Sekishu Ryu and Unshu Ryu, schools originated by two feudal lords, have had adherents

among the aristocracy.

Training in the tea ceremony

A visit to a professional tea-master's establishment is the best way to form an

adequate idea of the instructions. A group of three or four young women practise

under the teacher's guidance. One of them functions as hostess, while another takes

the part of the principal guest. The hostess arranges the various utensils in the

service room, which adjoins the tearoom. There is a set of rules prescribed for

bringing the utensils to the tea-room, in connection with which she has to observe,

for intance, the etiquette of sitting down and rising, entering and leaving the

room, opening and closing the sliding-doors. Owing to the necessity of performing

all these formalities in a small room and in the presence of guests, the pupil functioning

as hostess has to deport herself gracefully and adroitly.

The waiting-place for guests at the tea ceremony. Here, the joy of sharing hospitality

is expressed by those invited to a Cha no-yu party

Opening the sliding-door of the service room, the hostess makes a bow before entering

the tea-room. It is interesting to observe the elementary lesson of how to bring

in the water-jar, which has to be placed in a prescribed position. She leaves the

room to reappear immediately, holding the tea-caddy in the right hand and the bowl

in the left. She then makes another trip before she seats herself in front of either

the stationary hearth, or portable fire-brazier, as the case may be, according to

the season.

There are other rules for handling the caddy, and it is not a simple matter to dip

a ladle into cold and hot water in the right way. The bowl has first to be rinsed

ceremoniously, after which the water and tea- powder are thoroughly mixed in it.

There is scarcely any rule that is not based on reason and experience.

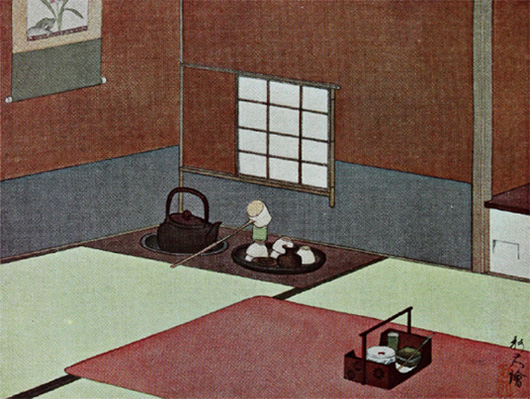

Putting powdered tea into the bowl

When the preliminaries are over, tea is served first to the pupil acting as principal

guest, who, in an actual entertainment, is the leader, in addition to being a guest

of honour. If it is koicha, or thick, pasty tea, she takes two or three sips and

passes the bowl to the second guest, after wiping the edge with a piece of pkper.

When the bowl reaches the last pupil, she is expected to drain the contents. The

empty bowl is returned to the hostess, who then complies with the leader's request

for the privilege of closely examining it. The principal guest has important duties

to perform from beginning to end, but the other pupils are not idle onlookers.

There is also a form of etiquette prescribed for the inspection of the caddy, which

the young lady functioning as hostess is pleased to offer, together with the spoon

and the bag for the caddy. These three are highly important articles in Cha-no-yu,

and may be valued treasures. When pupils practise the handling of such articles,

they are taught to observe the underlying practices to handle articles carefully,

the knowledge of the correct manner being useful on any occasion.

A detailed description of all these formalities in their proper order would be tedious,

but when performed by experienced persons, the whole procedure is pleasant to witness,

each step being smooth and graceful.

A tea master training his pupils

As an essential part of the training, pupils are also taught how to serve and partake

of the meal known as kaiseki. Even by Japanese, the eating of rice with chopsticks,

or the sipping of soup, is not quite so easy as might be imagined. Persons without

training are bound to blunder.

Those who have taken lessons in Cha-no-yu may forget much of what they have learned,

and may be out of practice, but the training received is not entirely lost. The

experience will save them from many a faux pas, even when making an ordinary call

in a Japanese home. Not a few middle-aged persons go to professional masters for

training. Cha-no-yu etiquette enables them to cultivate poise, grace, tranquility

and urbanity, all accomplishments making for refinement in manners.