TOURIST LIBRARY 10

Japanese Woodblock Prints

Written by

SHIZUYA FUJIKAKE, D Litt.

Published by

JAPAN TRAVEL BUREAU

Copyright 1959, sixth edition

Total 309 pages

Description

When most people think of Japanese wood-block prints, they think of Hokusai's prints

of Mt. Fuji and other landscape scenes created in the late Edo period. In fact,

the earliest Japanese wood-block prints date to the 11th century. While the early

prints in black and white were mostly for the purpose of reproducing religious texts,

the genre of "ukio-e" developed from a style of painting in the Edo period that

focused on the events of daily life. Gradually, the style progressed from prints

using red, yellow, and green, to realistic, intricate multicolor prints.

Enjoy these excerpts from "Japanese Wood-Block Prints"

The origin of "ukio-e"

Two women, a hand-colored print by Shigenaga Nishimura

Ukiyoe is not a very old word. It occurs first in a book entitled Koshoku Ichidai

Otoko by the celebrated author Saikaku Ihara (1642-1693), published in 1682. Genre

pictures that by their nature might well have been called ukiyoe, had been in circulation

before that date, and indeed such pictures may have been actually so called by the

people, with the result that Saikaku employed the term in his novel as a current

neoterism. And as such genre pictures became more and more popular, the term ukiyoe

came more and more into general use.

In those days the expression was applied to pictures depicting the ephemeral worldly

pleasures of gay life, so that their themes were taken from the gay quarters, the

theaters, and their neighborhood, which were the most popular places of public resort.

All through the Edo period the themes were taken from these same sources. The ukiyoe

painters thus chiefly portrayed gay girls and actors, but they also painted waitresses

in the so-called "tea-houses" attached to theaters, and geisha girls. Those who

ventured to represent the domestic life of daimyo (local lords), liatamoto (immediate

feudatories of the shogun), and other members of the military class, did so at the

risk of incurring the ire of the Shogun- ate and thus being thrown into prison.

For this reason the warrior class afforded the painters but few themes for their

pictures. Even the domestic life of the more sober tradespeople was not much represented

in ukiyoe. So the ukiyoe painters at first contented themselves with objective representations

of scenes in the gay quarters and in theater streets; they then depicted their indoor

life ; and finally went on to the portrayal of gay women and actors with all their

individual characteristics and peculiarities. In this respect, i. e., in the choice

of subjects, both hand-painted genre pictures and wood-cuts went through a very

similar series of changes.

From the foregoing it will be obvious that one would fall into a serious error if

one were to form an idea of the general manners and customs of the Edo period solely

from the genre pictures of the ukiyoe type, particularly from those which are known

as nishikie. The reader is, therefore, once more warned against the impression he

might get from ukiyoe of a highly colorful metropolis full of lovely women strolling

through its thoroughfares. He is asked to bear constantly in mind the extremely

narrow sphere to which the manners and customs shown in such detail in ukiyoe were

really confined.

A kitchen scene by Moronobu Hishikawa

Since the formal position of ukiyoe in the history of Japanese art depended on the

straightforward representation of prosaic urban manners and customs, it was inevitable

that they should have catered to the taste of the common citizen by depicting scenes

in the gay quarters and theatrical circles. Indeed, the ukiyoe painters far surpassed

all other schools of graphic art in the representation of life in such circles.

Extremely limited as was the social sphere from which the ukiyoe artists at first

obtained the themes, the general conception of the term ukiyoe (a picture depicting

the fleeting world or mundane life) was gradually extended to cover all phases of

life, with the result that the spheres of life represented by ukiyoe became correspondingly

enlarged. Ukiyoe painters, moreover, sought to meet popular demands for other kinds

of pictures, such as those of wrestlers, warriors, dolls, children, etc., and pictures

to adorn battledores, picture-books, illustrations for novels, and so forth.

Landscape prints

But the most artistic developments occurred in prints of landscapes, flowers, birds,

etc,. Such pictures, showing as they did the beauties of Nature, could hardly be

called ukiyoe in the proper sense ; but in the sense that they were produced by

ukiyoe artists, prints of birds and flowers constitute a legitimate subject of study

by students of the ukiyoe proper. As for landscape prints, they may be regarded

as backgrounds of portraits or genre pictures greatly enlarged and made into independent

pictures. Most of them, however, are not simple representations of scenery, for

they combined with them things Japanese, both inanimate and personal, as well as

the Japanese taste and love of travel. It thus seems natural that landscape prints

should have come to be treated as a kind of ukiyoe. When the principles of linear

perspective, familiar to Western artists, were made known to Japanese painters,

the ukiyoe men, untrammelled by old-established rules of painting, eagerly learned

the new technique and applied it to their own wood-cuts. The tendency began about

the Kyoho era (1716-1735), and one of the pioneers in this movement was Masanobu

Okumura. The introduction of the peep-show with suitable pictures, and of the art

of copperplate engraving, gave fresh impetus to the technical development of landscape

painting. Toyoharu Utagawa and Kokan Shiba attracted general attention as masters

in this new field. But it was Hokusai Katsushika, Kuniyoshi Utagawa, and Hiroshige

Utagawa who, by the skilful application of the newly-introduced principles of linear

perspective, and the technical excellence of copper engraving, brought landscape

printing to a culmination.

Sudden Shower at Shono (from the "53 Stage-towns of the Tokaido") by Hiroshige Ando

The impasse to which the art of xylography had come, near the end of the Edo period,

owing to the impossibility of further progress in the portrayal of lovely women

and actors, was forced open, as it were, by the triumph of these artists in landscape

wood-block printing. Landscape prints, moreover, appealed strongly to the popular

taste because just about that time, the inhabitants of the larger towns had become

much interested in travel, and travel literature was in great vogue. And of the

three artists above-mentioned, Hiroshige was perhaps the most Japanese in his attitude,

for he not only did justice to the various local features of rural Japan, but gave

objective pictures of its climate and weather in all their varied aspects. There

are traceable in Hokusai's landscapes a good many elements of Chinese taste, and

he is more subjective than objective. Kuniyoshi's pictures are mainly Occidental

in expression, and strike me as too realistic. Each of the three masters perfected

an artistic style of his own, and thev have thus won the admiration of European

and American connoisseurs, with the result that they have exerted an important

influence on the Western art of painting.

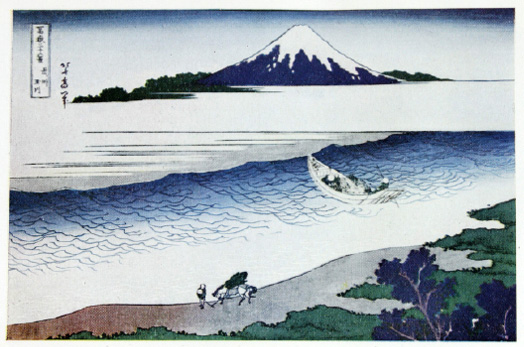

Mt. Fuji as seen from Tamagawa (from the "36 views of Mt. Fuji") by Hokusai Katsushika

The rise of the wood-block print

Down to the middle of the 17th century the fine arts had been the province of only

the warriors, the nobility, and the priests. From about that time the common people

grew steadily in importance, and they created and developed a culture of their own.

Ukiyoe, painted by hand, were admired and treasured at first only by wealthy tradesmen

in the towns, but the further development of plebeian culture taught people of the

middle and lower classes to demand and appreciate works of art. It was thus with

the idea of enabling such people to enjoy inexpensive works of art that the popular

art of picture-printing was brought into being. It was, therefore, necessary that

such prints should be of a sufficiently high quality to be appreciated as excellent

art products rivaling the entirely hand-made ukiyoe. Their very size or shape was

such as to render them suitable for appreciation. Some were large enough to be made

into kakemono or hanging scrolls, or into gaku-men or framed pictures; some could

be collected into pictorial albums ; while others were of a size adapted for pasting

promiscuously on walls, fusuma (paper sliding-doors or screens), and byobu (paper

folding-screens). In most cases each picture was complete in itself, but sometimes

several wood-cuts formed one set or series. Of those prints which formed albums,

usually a dozen constituted a series. All these facts go to prove what has already

been said, viz., that these prints were meant to be democratic substitutes for the

hand-painted pictures treasured in aristocratic circles.

Kasamori-Osen (a popular daughter of a tea-house) By Harunobu Suzuki

Simultaneously with the development of these artistic prints, there also developed

the art of book-illustration and the publication of what were known as picture-books

(of which the pictures rather than the reading matter formed the principal contents).

Over a dozen pictures made up a picture-book, almost every picture having a few

words of explanation written on it. Representing as they generally did contemporary

manners and customs, they greatly excited the curiosity of would-be purchasers,

and were thus the most popular works of art of the day.

It will amply repay our efforts to investigate the causes that led to the birth

of this consummate type of colored broadside known as nishikie, which indeed marked

a distinct epoch in the history of our art of engraving.

It should be remarked in the first place that the nishikie was not the result of

the combined efforts of painters, engravers, and printers, but that there was a

group of men who acted as their guiding spirits and made suggestions and plans for

those artists, thus rendering it possible for them to produce such superb works

of art. This group was composed of writers of comic and satirical verse, known as

kyoka (literally " mad songs "). Some poets of this ty pe in those days took a deep

esthetic interest in prints used as frontispieces of books, and they devised new

and artistic color prints for this purpose. Among those comic poets were many young

men who were sons of wealthy tradesmen in Edo, and being free from the cares and

worries of earning a livelihood for themselves, they could afford to devise or design

artistic color prints of purely esthetic merit. It was thus, chiefly by these rich

versifiers that benizurie (crimson prints) were raised to the level of nishikie

or brocade prints.

In the earlier specimens of nishikie one sees such signatures as the following:

Hakusei, Ko

Harunobu Suzuki, Painter

Goryoku Endo, Engraver

Koshi Yumoto, Printer

Before the Mirror by Ito Shinsui

This means that the piece was painted by Haru- nobu Suzuki, engraved by Goryoku

Endo, and printed by Koshi Yumoto. The expression " Hakusei Ko " means a new type

of print invented by the comic poet Hakusei. It signifies, in other words, that

the nishikie was produced by a literary man with a keen appreciation for color prints,

acting as a sort of conductor to a trio composed of a painter, an engraver, and

a printer, all four working in perfect harmony. It is no wonder that something entirely

new and highly artistic should have been created. Many new technical devices went

to the making of the nishikie, the most notable of all being those which facilitated

the artistic coloring of the pictures. Not only was the work of engraving the coloring

blocks executed with great skill, but the colors were increased in number. The paper

used for printing iiishikie was called liosho, which was of a higher quality than

the paper used for benizurie, so that it brought out the different colors and tints.

It was fortunate for the art of chromoxylography that it thus enlisted into its

service literary men of high esthetic sensibility, as well as skilful painters and

equally dexterous engravers and printers, who united their minds and efforts to

lift it to a higher plane of excellence than it had ever attained before.