TOURIST LIBRARY 8

Ceramic Art of Japan

Written by

Tadanari Mitsuoka

Published by

JAPAN TRAVEL BUREAU

Copyright 1956

Total 215 pages

Description

Ceramic arts came to Japan from Korea and China. Throughout the centuries, styles

and techniques were imported to Japan and adapted to the Japanese aesthetic. In

the beginning, ceramics were expensive items and everyday bowls were made of wood.

As technology such as kilns built into hillsides were imported, ceramicists could

use higher firing temperatures and produce more items at once. Japanese ceramic

styles are often associated with a particular kiln. They vary widely, but the styles

considered to be more original to Japan were influenced by the tea ceremony and

aesthetic preferences of tea masters.

Please enjoy these excerpts from Ceramic Art of Japan.

Seto-ware one of the first glazed styles in Japan

In the 9th century the glazing method of celadon was also introduced from the Continent.

As it required high-fired baking, the glaze was applied in kilns in Owari province

(in the neighborhood of Seto, Aichi prefecture) which were the most advanced of

all Sue ware factories, and thus imitations of Chirese celadon began to be produced.

The Owari Seiji (celadon) or Owari Jiki (porcelain) as referred to in the records

of those days means this type of celadon.

About the 12th century the manufacturing center of this Owari celadon shifted to

Seto, and the first step was taken of the development of Seto ware which was destined

to secure the most important position for many centuries in the ceramic art of Japan.

The zenith of the prosperity of Seto factories in the middle age (1186-1568) was

reached towards the end of the Kamakura period (1186-1333) and in the early part

of the Muro-machi period (1334-1573), i. e. from the 14th to the15th centuries.

Seto ware: Lotus-patterned jar with amber

glaze

(14th cent., Aichi pref.)

By. T. Ichihara)

To review the productions of Seto kilns in the above-mentioned period, the principal

kinds of pottery include jars, pots, pitchers, bottles with a turnip-shaped base,

vases, incense-burners, shallow bowls, and Tem-moku-type tea-bowls. Some of the

pots have four handles and others are wide-mouthed, while among the vases there

are those with fixed loop handles or fish-shaped handles, those of a mallet shape,

or of the shape of a wine jar with foliate brim. It is astonishing to see how varied

they are merely in respect of shape.

The remains of the Seto kilns of those days are still now discovered in large numbers

in the hilly districts near Seto town. They tell us how prosperous pottery manufacture

was in those times, and how enormous was the production. Although equally local

in scope, Seto pottery is of far greater importance than the lead-glazed pottery

that preceded it, whether socially, or from the standpoint of the history of ceramic

art. If the lead-glazed pottery of the 8th century is noteworthy in an historical

sense that it meant the first advent of glazed wares in Japan, the Seto pottery

of the 14th and 15th centuries may be said to mark the actual starting point of

the growth of Japanese ceramic industry in that it turned out articles of advanced

style and carried on production on a large scale.

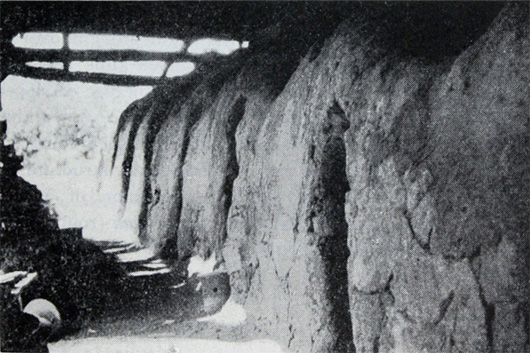

Nobori-gama (sloped kiln), Mashiko kiln, Tochigi pref.

Ceramic flourished in Edo period

The beginning of modern times, extending over the closing years of the 16th century

and the early part of the 17th century, was the most significant period full of

epochal events in the history of ceramic art in Japan. Before that time, the principal

productions were on the whole earthenwares, although glazed wares were manufactured

locally. It may be called the earthenware age. In modern times, factories were set

up and made a steady growth first in western Japan and then in the other parts of

the country. Besides pottery, porcelain began to be manufactured, while many new

departures were made in the technique of decoration. Single-chambered kilns were

replaced by the nobori-gama (sloped kiln) of large-scaled and more efficient type,

which made production in large quantities possible. Their development was so remarkable

that they amply satisfied the large demand of the rising class of commoners. Particularly,

the Edo period (1615-1868) was worthy of the name of "pottery and porcelain age"

as it is often said. For it was in this period that Japanese ceramic art attained

maturity, burst into flower, bore fruit and developed a truly characteristic expression.

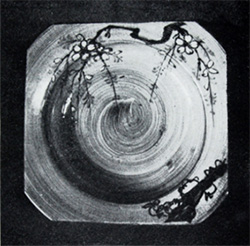

Kutani ware: Enamelled dish with grape design

(17th cent., Ishikawa pref.)

A specimen of Ko-Kutani (early Kutani ware).

The dawn of modern Japan stimulated the ceramic industry, and signs of fresh activity

were seen in this field. Wares of a new type influenced by Korean Yi dynasty (1392-1910)

pottery and porcelain were produced at Mino kilns (Gifu prefecture) belonging to

the Seto type, and also at Karatsu kilns, while in Kyoto appealed the Raku pottery

which similarly copied the Yi dynasty style. This active and progressive spirit

of formative art to adopt advanced foreign technique and style was further displayed

at the time of Toyotomi-Hideyoshi's invasion of Korea towards the end of the 16th

century, when the technique and style of Yi dynasty pottery and porcelain were introduced

as the only useful by-product of an otherwise useless campaign. In various parts

of western Japan, sloped kilns of Korean type were set up by potters brought from

Korea with the Daimyos. As a result, Arita factories (Saga prefecture) and kilns

in many other places were newly established. It was this large-scale transplantation

of Korean ceramic technique that laid the foundations for the prosperity of pottery

and porcelain industry in the Edo period. Of course those factories turned out wares

of Yi dynasty style at first, but soon the Arita kilns manufactured porcelain, unknown

in Japan until then. This advent of porcelain made it possible to imitate the more

advanced enameled porcelain of China which had long been the object of aspiration

by Japanese, together with, or ever more than, the Yi dynasty pottery. Thus the

technique of over-glaze decoration was eagerly studied by the native potters, and

porcelain wares modelled after the enameled ware of the late Ming and early Ch'ing

dynasties came to be manufactured for the first time in Japan. The growth of this

porcelain and over-glaze decoration was destined to form one of the most important

features of ceramic art in the Edo period.

The lead glaze pottery, Owari celadon, and Seto pottery wares in the Middle Ages,

of which we spoke above, were all manufactured under the stimulus of the aspiration

of our people for the advanced culture on the Continent. The imitations of Yi dynasty

pottery and porcelain as well as of porcelain in the late Ming and early Ch'ing

dynasties resulted from Japanese admiration for the cultural advancement of Continental

countries. This active interest shown by our people in advanced cultures was an

essential factor in the growth and improvement of Japanese ceramic art.

Characteristic features of Japanese ceramics

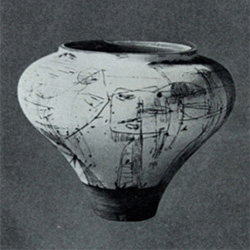

Utsutsugawa ware: Brush-marked bowl with cherry-blossom design (17th cent., Nagasaki

pref.)

The design is painted on the brush-marked ground with white slip, copper-green glaze

and brown iron oxide. Utsutsugawa ware belongs to the family of brush-marked Karatsu

ware and is noted for its elegance and refinement.

When we compare Japanese works of ceramic art with those of China or Korea, upon

which they were originally modelled, it strikes us first of all that their expression

is gentle and suave. For example, the Seto wares of middle ages, which in form are

imitations of Sung and Yuan porcelain, show nothing of the sharpness, rigidity and

vigor that marks their Chinese prototypes, but manifest a feeling which is serene

and purely Japanese. Also the comparison of E-Shino (painted Shino ware) and E-Garatsu

(painted Karatsu ware) with Yi dynasty pottery brown-painted with iron oxide reveals

that the rude vigorousness of the Korean ware is absent in those Japanese productions,

which are overflowing with the graceful sentiment of the Japanese people. This characteristic

feature is the more clearly perceived when we compare Kakiemon-de, Iro- Nabeshima

(enamelled Nabeshima ware), or Ko-Kiyo-mizu with decoration in colors to the Chinese

enamelled porcelain of the late Ming dynasty or the early Ch'ing dynasty. Further,

if one turns to Raku ware which of all the native wares is most typically Japanese,

one will be convinced of these characteristics.

In fine, the characteristics of expression common to Japanese pottery and porcelain

is traceable to Japanese taste, temperament and character. It is ultimately related

to the fact that the devotees of tea-cult who most plainly represent the Japanese

taste like the so- called enamelled gosu porcelain and Ko-Sometsuke blue and white

best of all Chinese wares, prefer pottery to porcelain, and of all varieties of

tea bowls care most for those which are agreeably rough to the touch, and particularly

for Raku ware bowls. The Japanese have an inclination for anything soft in tone,

whether visual, tactual, or auditory.

While it is especially characteristic of Chinese porcelain to contain regular, restrictive

elements in their design, the Japanese productions are marked by irregularity and

freedom. The former are intricate and simulative, while the Japanese wares are simple

and homely.

Variety in Japanese ceramics

Kumakura-Junkichi, one of the most promising ceramists of present-day Japan, has

a modern style with an intellectual touch, which is conspicuous in his designing

and modeling.

Most production in the Edo period have the names or monograms of the makers or kilns

impressed, engraved, or painted on them. The kinds of wares which bear such names

or marks probably exceed ten thousand in number. As each kind of those inscribed

production has some features which distinguish it from others, this immense variety

may also be regarded as a characteristic of Japanese ceramic wares. The cause of

this last feature can be sought in the feudal system of the Edo period, under which

the country was divided into numerous clans, large and small, each forming a cultural

sphere by itself, and in the national isolation of long duration which in the long

run directed the interest of the people to small and minute matters.

Japanese ceramics as appreciated by tea masters

Particularly as regards tea bowls, they attach importance to the feel," or how the

wares are felt by the lips or the fingers. They take the greatest delight in a soft

feel, and the tea bowl of Raku ware meets this requirement most satisfactorily.

They also make much of tedori, or the feeling of weight on the hand. In this case,

too, moderateness is made the most of. With regard to the degree of contraction

in the baking, too much stiffness is disfavored. This is also related to what has

been stated above. It is also because freedom from restraint is sought that keshiki

or variation is cared for. Again the tea-devotees enjoyed the exquisite charm of

the faint wet color presented by a pitcher or a flower vessel of unglazed Bizen

or Shigaraki ware when sprinkled with water. Those tea-devotees were certainly unsurpassed

in the subtlety of senses. It is needless to say, however, that the taste of those

votaries of tea-cult came from the characteristic temperament of the Japanese. Indeed,

no words are more aptly expressive of the Japanese taste than those often used by

the tea-masters, zangurishita "an agreeably rough touch."

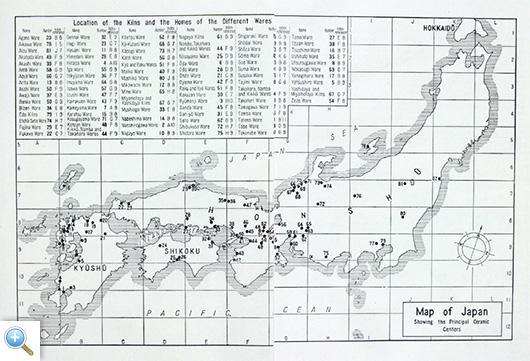

Map of ceramic styles in Japan