TOURIST LIBRARY 7

Japanese Architecture

Written by

Hideo Kishida, D. Sc.

Published by

BOARD OF TOURIST INDUSTRY,

JAPANESE GOVERNMENT RAILWAYS

Selling Agents by

MARUZEN CO. LTD., TOKYO

JAPAN TOURIST BUREAU TOKYO

Copyright 1940, third edition

Total 137 pages

Description

The most important and fundamental characteristic of Japanese architecture is that

it is based on the skilful use of various woods. Some other distinctive characteristics

include a preference for the natural wood color over paint, exposed columns and

other structural elements, and preference of the straight line over the curved.

There are many examples of tradition architecture in Japan, including Sinto shrines,

Buddhist temples, houses, castles, palaces and tea houses.

Enjoy these excerpts from "Japanese Architecture"

Japanese roof styles

It is said that the beauty of Japanese architecture consists in the variety of roof

design. The roof is one of the most important elements in Japanese architecture

both in function and expression. In wooden buildings, especially in Japan where

we have rather heavy rains, it is not rational to make the roof flat, as is the

case with reinforced concrete buildings.

As for roof forms used in Japanese architecture, there are several kinds such as

the gabled roof, hipped roof, pyramidal roof and hipped roof with gables (irimoya).

The last-named is a type of roof peculiar to Japan, and is quite foreign to Western

architecture. The grand and imposing tiled roof of Buddhist temples, the light and

solemn hiwada roof (covered with small thin pieces of hinoki) of Sinto shrines,

the picturesque thatched roof of country houses, the elegant and tasteful roof of

tea ceremony kiosks, the calm and subdued tiled roof of Japanese dwelling-houses,

the magnificent and refined roof of old castles ; all bear witness to the wonderful

beauty embodied in every variety of Japanese roofs.

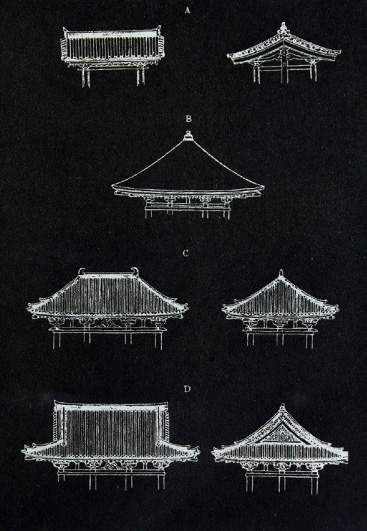

THE FOUR FUNDAMENTAL FORMS OF JAPANESE ROOF DESIGN

A. Kirizuma (gable roof) B. Hogyo (square pyramidal roof) C. Sityu or Yosemune (hipped

roof) D. Irimoya

There are many curved lines in the design of the Japanese roof, and the most remarkable

are the curves of the eaves and the slope of the roof. The application of curved

lines in Japanese architecture is based on a style imported from the Asiatic Continent,

and dates from about the middle of the 6th century.

Eaves in Japanese architecture

The prominent projection of eaves is another noteworthy characteristic of old Japanese

buildings. This serves to increase the feeling of stability and to harmonize the

form of the building. But this projection of the eaves is not for decoration only

; it was born of necessity. As summer in Japan is a season of rain, and the atmosphere

then is very sultry, the people naturally like to open the windows to have good

ventilation even during heavy rainfall.

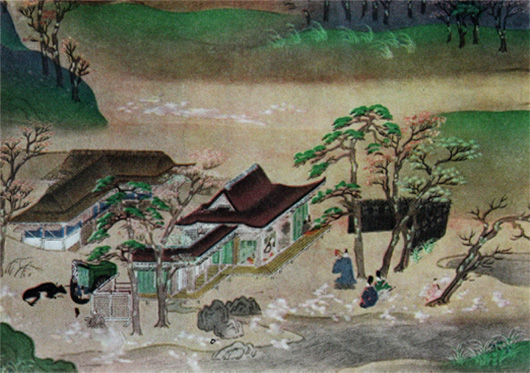

Old dwelling house from "senzui byobu" series of screen pictures

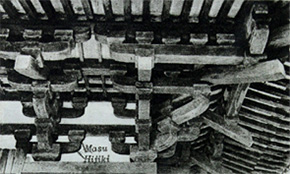

"Masu-gumi"

"masu-gumi"

"Masu-gumi" (masu and hiziki) is a structural detail for supporting the overhanging

eaves, and one of the most remarkable details of Japanese architecture. This device

is one which is chosen to this day whenever an architect desires to obtain a pure

Japanese effect. " Masu-gumi " was originally a part of the construction itself,

though at the same time it adequately embodied a decorative effect.

It is an ingenious constructional detail which came originally from the Continent

together with the introduction of Buddhistic architecture in the middle of the 6th

century but in course of time it has come to be one of the most typical of Japanese

architectural devices, as if it were an intrinsic symbol of Japanese Masu-gumi (masu

and hiziki) architecture. Though many variations old form are found in " Masu-gumi,"

according to the different periods, the principle of structure is identical: first,

projecting hiziki to the front or to the sides, then the placing of masu on the

hiziki at varying distances, after which hiziki are projected on them, and the same

process is repeated.

For this purpose, and also to prevent direct sunshine from penetrating into the

room, the wide over-hanging eaves are indispensable. In winter, however, this projection

of the eaves does not prevent the sunshine from entering and warming the room, as

the sun travels low throughout the mainland of Japan during this season. This marked

projection of the eaves often extends as much as 18 feet from the wall, as in some

Buddhist temples ; and as heavy tiles are laid on it, it requires wise and solid

devices of construction. The weight is skilfully balanced by the application of

hanegi, the principle of which somewhat resembles that of a balance. Under the surface

of the eaves, tarnki (rafters) are arranged in rows to counteract the monotony of

the wide projecting eaves.

Sinto Architecture

The Sinto shrine may well be considered the architectural symbol of ancient Japanese

culture. The Sinto shrine is a building dedicated to Sintoism, the national religion

of Japan, which, originating in Nature and ancestor worship and based upon a firm

foundation, has prevailed since ancient times and has dominated the spiritual life

of the Japanese nation. Even when Buddhism and Confucianism were introduced into

Japan, Sintoism harmonized with them and it has come down to the present day. Many

Sinto shrine buildings have been preserved unchanged in their original form through

the ages.

There exist, at present, over 150,000 Sinto shrines in Japan. It may indeed be said

that where one sees a a forest there one may find a sacred place entirely secluded

from worldly life.

Original sinto shrines from ancient times

We find four principal forms of Sinto shrine building in ancient times: Taisya-zukuri

(zitkun means architectural type), Otori-zukuri, Sumiyosi-zukuri and Sinmei- zukuri.

Typical examples of these four types are : Izumo- Taisya (Taisya means great shrine),

Otori-zinsya (.zinsya means Sinto shrine), Sumiyosi-zinsya and Ise-Daizingu (Daizingu

means great shrine).

Ise-Daizingu (Uzi-Yamada, Mie Prefecture)

There are two shrines at Ise; one is the Geku (outer shrine) and the other the Naiku

(inner shrine). These shrines are built on the same principle and in accordance

with the same forms, representing a more developed stage in the art of Sinto shrine-building

than the three types mentioned above. The sublime and solemn atmosphere of Sinto

shrines pervades the whole precinct of the Ise Grand Shrine, and it is here that

this atmosphere attains its highest expression. It is, so to speak, the symbol of

Japan. Japanese spirit and taste will never fail to be recognized here.

Ise-Daizingu is the most sacred place in Japan. Spirit, nature and architecture

are here united, and create a unique atmosphere which gives the visitor the impression

of having been transported to the land of gods. The Ise-Daizingu is the highest

embodiment of the Japanese spirit, and its architecture is the purest expression

of original and genuine Japanese taste.

Shrines exhibiting Chinese influence

The original Sinto shrines such as the Ise-Daizingu, Izumo-Taisya and bumiyosi-zinsya

were of pure Japanese style. But owing to the introduction of Buddhist arts, continental

influences came to bear upon shrine building, so that new and compromised styles

of shrine building developed during the 8th century. In the latter part of that

century, there evolved such new styles of shrine building as the Kasuga-zukuri,

Nagare-zukuri, Hatiman- zukuri and Hiyosi-zukuri. Typical examples of these new

styles are the Kasuga-zinsya, Simogamo-zinsya, Usa-zingu and Hie-zinsya.

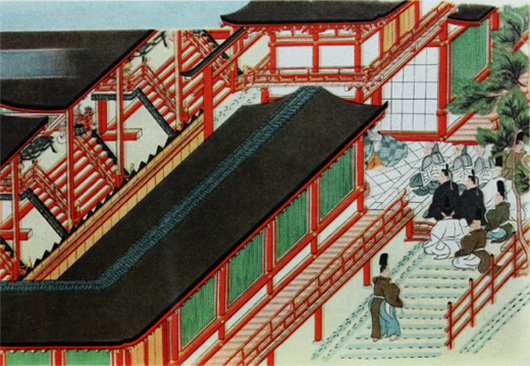

Kasuga-zinsya shrine, from "Kasuga-gonen reigen-ki" picture scroll …

Kasuga-zinsya (Kasugano, Nara)

No visitor to Nara will fail to go to this beautiful shrine, its rich vermilion

colour contrasting with the green of the old trees of the surrounding forests. It

was founded about the middle of the 8th century, but it took its present form of

Kasuga-zukuri at the beginning of the Heian Period (784-1185). One of its architectural

characteristics is the eaves (in Japanese kohai) which project over the front stairway

and form a unique design in harmony with the front gable. The bright colours the

wood, and the complex curves of the roof show the influence of continental styles.

Buddhist architecture

It is needless to say that religion is often responsible for creating styles of

architecture. Generally speaking, Japanese architecture has remarkable Buddhistic

elements. This naturally comes from the fact that Japanese culture itself is based

to a great extent on Buddhism.

It was in the 13th year of the Emperor Kinmei's reign (552 A.D.) that Buddhism was

first introduced into Japan from Kudara, a part of Korea in those days. With the

introduction of this religion, continental Buddhistic styles of architecture came

to be eagerly copied, and greatly influenced the building art in Japan.

There are many sects in Buddhism, and those which were introduced into this country

and which flourished in the Asuka and Nara Periods (552-783) were the so- called

Nanto-Rikusyu (Six Sects of Nara): Sanron-syu, Kusya-syu, Hosso-syu, Zyozitu-syu,

Kegon-syu and Ritu- syu. In the beginning of the Heian Period (784-1185), the two

sects of Tendai and Singon were introduced from China. In the Kamakura Period (1186-1392),

the Zen sect was introduced from the China of the Sung Dynasty ; while, on the other

hand such sects as the Zyodo-syu, Sin-syu, Nitiren-syu, Zi-syu and Yuzunenbutu-syu

were founded in Japan. In the Edo Period (1615-1867) the Obaku sect was introduced

from the China of the Ming Dynasty.

Thus, since Buddhism was first brought over from the Continent, many different sects

in succession have been introduced from China, while many new sects have been founded

in Japan itself. Generally speaking, each successive government adopted a generous

policy toward all these different sects of Buddhism, and thus each sect developed

parallel to all the others. It is on account of this fact that we can fortunately

see today typical Buddhist temple buildings in Japan which represent the development

of each sect throughout the periods of her history. This is not so in China, where

all sects except the Zen have perished.

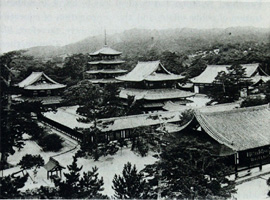

Horyu-zi Temple (Horyu-zi, Nara Prefecture)

Bird's eye view of Horyuji temple

This temple was completed in the 15th year of the Empress Suiko's reign (607 A.D.),

and is one of the buildings of greatest historic value which remain in Japan today.

It seems almost miraculous that the buildings of the Horyu-zi Temple should be more

than 1,300 years old. The wood used there is a superior kind of htnoki, and the

climate in that province is happily well suited for the preservation of wooden buildings.

Moreover, the unvarying respect paid to this temple by the people has proved effective

in making perfect preservation possible.

Todaiji Temple (Nara)

Nan-daimon of todaiji temple, nara

At the beginning of this period the Zen sect was introduced, and with this new sect

a new building style was brought over from the China of the Sung Dynasty. We call

it " Kara-yo " (kara means foreign and means style). The distinguishing features

of the " Kara-yo " style are seen in the arrangement of the location of buildings

: the principal buildings being arranged in a row on the central axis as in the

Sitenno-zi style of the Asuka Period. The architectural and decorative treatment

of the Kamakura Period shows a great change when compared with former styles. On

the whole the effect is sombre and heavy. A good example of this style which now

exists is the Syariden of the Engaku-zi Temple, Kamakura.

In this period, another style known as the " Tenziku- yo," a slight variation of

the " Kara-yo " style, was developed. The Daibutu-den and Nan-dai-mon (great south

gate) of the Todai-zi Temple, Nara, are specimens of this style, the remarkable

features of which are to be observed in the details of " Masu-gumi " : masu and

hiziki projecting only to the front and not to the sides..